[Note: Complete text in English below]

كيف يصنع المواطنون فرقا في النقل للقاهرة

القاهرة، مصر، النقل، المناطق الحضرية، التخطيط الحضري

نهاية عنوان المقدمة

المؤسس المشارك ل”القاهرة من الأساس” نيكولاس هاملتون يحاور مؤسسا “مواصلة للقاهرة” محمد حجازي وحسام العقدة.

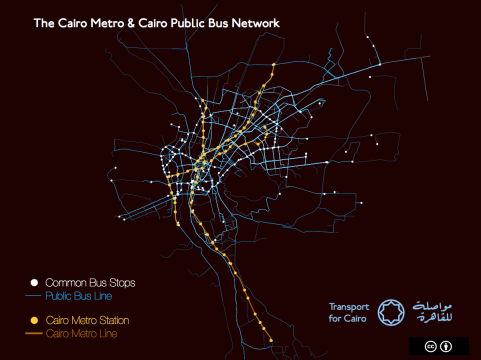

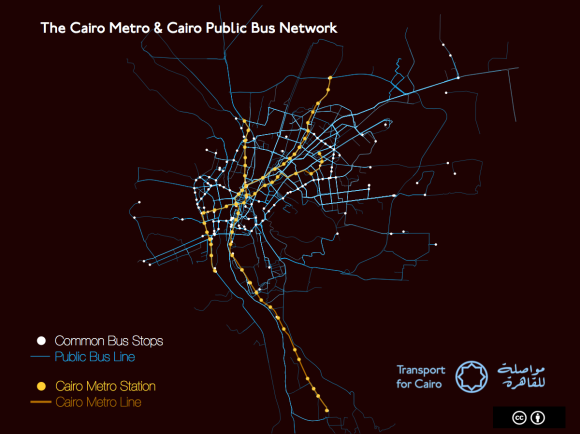

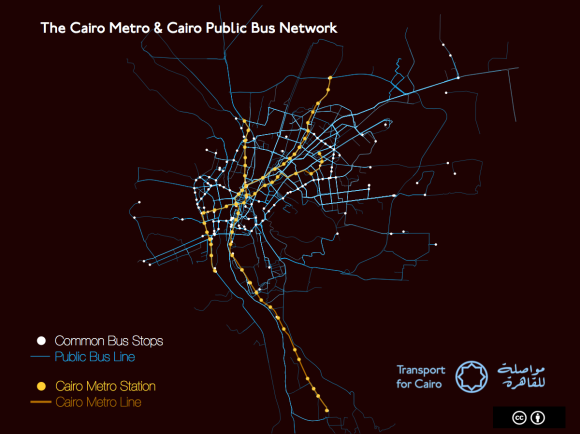

.رسم توضيحى لخطوط أتوبيات النقل العام ومترو القاهرة- الطرق والمحطات بواسطة “مواصلة للقاهرة”

كيف بدأت “مواصلة للقاهرة”؟

حسام: ذات يوم كنت أسير في الطريق وتلقيت مكالمة مشوشة من حجازي -صديقى منذ زمن بعيد- وعندها أخبرنى عن مشروع قد علم عنه للتو في نيروبى.

حكي لي حجازى عن الفريق الذي وضع خريطة لشبكة النقل “غير الرسمية” في المدينة وكيف جعل تلك البيانات متاحة للجميع. وكان المشروع يدعي “Digital Matatus”.

وقال حجازي أنه يرى أن بامكاننا القيام بنفس المشروع في القاهرة حيث تغطى المواصلات الغير رسمية جزءا كبيرا من احتياجات النقل في المدينة. وقد تحمست جدا للفكرة حتى أننى تمهلت عن المشى قليلا، وذهبت إلى أقرب مقهى بالجوار، وفتحت جهاز الكمبيوتر المحمول الخاص بى وبدأت البحث. كنت قد أصبحت مهووسا بفكرة كيف بامكاننا -كمواطنين- أن نوفر لملايين المصريين الوصول إلى تلك المعلومات المفيدة حول شبكة النقل الحالية وتمكينهم من إستخدام هذه المعلومات لتحسين حياتهم اليومية. وفي ذلك اليوم حددنا الأساسيات المنهجية لأبحاثنا ومن هنا بدأت “مواصلة للقاهرة”.

ولكن ما هي علاقة البيانات بالمواصلات داخل المدينة؟ وماذا تأمل أن يحققه هذا المشروع؟

حسام: إن الهدف الأساسى من هذا المشروع هو تسهيل إستخدام الناس لوسائل النقل العام في القاهرة. قبل أن تتمكن من التفكير في إدخال تحسينات على نظام النقل، يجب عليك أولا أن تفهم النظام الذي تملكه. ونريد إيصال تلك البيانات لأكبر عدد ممكن من الناس. نريد أن يستخدمها سائقى وسائل النقل العام والخاص والباحثين ومطوري التطبيقات الخاصة بالمواصلات والجمهور أيضا، لفهم النظام كما هو.

محمد حجازي: إذا ما قمت بزيارة موقعا الكترونيا خاصا بتخطيط الرحلات مثل Gooogle maps أو Bey2ollak– والذي يعد واحدا من أشهر التطبيقات في مصر اليوم- فسوف يزودوك باتجاهات للقيادة فقط، وربما في بعض الأحيان اتجاهات للمشي أيضا، ولكن ليس في استطاعتهم ان يزودوك بالخيارات المتاحة لك لاستخدام شبكة المواصلات العامة، لأن تلك المعلومات والبيانات لم يتم جمعها بالأساس كما أنها غير متاحة حتى الآن أيضا، الأمر الذي يشجع المواطنين على استخدام سيارات النقل الخاصة لعدم وجود مصدر موثوق للمعلومات يمكن الاعتماد عليه بخصوص خيارات النقل العام.

لقد بدانا فكرة وضع مخطط لخطوط الميكروباصات بالقاهرة حيث أنه لا توجد مخططات لهذا لذلك النوع من المواصلات حتى الآن، وقد حاولنا دمج تلك المعلومات مع المخططات الحكومية عن وسائل النقل العامة الرسمية التي تشمل الاتوبيسات وخطوط المترو، والتي يمكن اتاحتها سواء للجمهور أو مطوري البرمجيات أو الباحثين. ولكننا سريعا ادركنا عدم وجود هذه المعلومات عن المترو أو الاتوبيسات المملوكة للحكومة، وبالتأكيد لا توجد للميكروباصات.

لصنع خريطة وبرنامج قوي لتخطيط الرحلات فأنت فى حاجة الى بيانات قياسية عن أكثر من شىء، مثل الطرق، والمحطات، وطول الطرق. تحتاجها في شكل نوع من برمجة البيانات يسمي GTFS أو General Transit Feed Specification.

وهذا ليس سهلا في أفضل الظروف، ولكننا بحاجة لفهم مدي حجم شبكة المواصلات في القاهرة وعمق تعقيدها. فالقاهرة الكبري يسكنها نحو 18 مليون نسمة، يصلوا إلى 20 مليون خلال أيام الأسبوع خلاف العطلات، ويزدادوا سكنيا وعمرانيا بشكل متسارع جدا، ويحتوي مترو القاهرة على 61 محطة، بطول 65 كم ومازال يتوسع ويمتد، وهناك مايقرب من 450 الي880 خط أتوبيس مملوك للحكومة، ولكن كلاهما لا يشبع الخدمات المطلوبة للنقل في القاهرة، لذلك فلدينا أيضا خدمات النقل غير الرسمية من الميكروباصات، والتي تنقسم داخليا هي الاخري إلى هؤلاء المصرح لهم بالعمل بخطوط سير محددة، وآخرين غير مصرح لهم بذلك ويسلكون مسارات مختلفة اشبه ماتكون بالتاكسي المشترك.

لا أحد يعلم حقيقة عددهم بدقة، وماهي الطرق التي يسلكونها، ولا عدد الافراد الذين يستقلوها، ولكن التخمينات تقول بان ذلك النوع يغطي 40% من احتياجات النقل بالمدينة، والتي تكاد تساوي نسبة مستخدمي النقل العام.

اذا ماهي طريقة سكان القاهرة للحصول على معلومات السير حاليا؟ وكيف تختلف عن الطرق الاخري؟

حسام: إن معظم المعلومات الخاصة باستخدام شبكة النقل العام في الوقت الحالي يتم تداولها شفهيا، وتوجد ضبابية كبيرة حول مدي صدقها والخيار الأسرع المتاح بالفعل، وباتاحة كافة المعلومات للجمهور ستكون معرفة أسرع المسارات وأرخصها في متناول اليد للجميع، سيكون بامكان التطبيق الخاص بنا على أي تليفون ذكى ان يخبرك كيفية الوصول لأي مكان ومدي مدة رحلتك اليه تقريبا.

محمد حجازي: باستثناء المترو فالمعلومات المتاحة لي كمواطن قليلة جدا. تقوم الحكومة بنشر ملف pdf لمسارات الطرق الخاصة بأتوبيسات النقل العام فقط، وهذا هو كل شيء. حتى عند توفر تلك البيانات فانها تكون غير متاحة للعامة ولايمكن استخدامها أيضا لتخطيط الرحلات.

هل نحتاج اذن لهاتف ذكي حتى نستفيد من “مواصلة للقاهرة”؟

حسام: هناك تصور خاطئ كبير عن أن الناس في الدول النامية لايملكون هواتف ذكية، في مصر. مستخدمي الهواتف الذكية – الذين يملكون أيضا خططا للانترنت من خلال الهاتف- يصل إلى 15.5 مليون مستخدم، والعدد في تزايد مستمر، ومن المتوقع على مدي السنوات الثلاث القادمة أن يرتفع العدد إلى 28 مليون مستخدم، ما يمثل أكثر من 50% من نسبة الشباب بالدولة.

ميني باص قطاع خاص يعمل بتصريح من السلطات الحكومية “رخصة المشاع الإبداعى CC-0”.

محمد حجازي: دعني أوضح تصورا آخر خاطئا، مستخدموا النقل العام ليسوا فقط من الطبقة الفقيرة، كل الناس يقومون باستخدام وسائل النقل العامة، ومستخدمو الهواتف الذكية أيضا يزدادون في وسائل النقل العام، هذه حقيقة.

كل مكان في العالم الآن أصبح مغطي بشبكات الإنترنت اللاسلكية wifi وشبكات الاتصالات تمتد وتعمل حتى بداخل أنفاق المترو. وأيضا في أثناء.

يمكن إنتاج خرائط مطبوعة يمكن حملها. واخيرا هناك تصور خاطئ نستطيع مناقشته، حيث أنه ليس بالضرورة ان تكون التغيرات على مستوى عالمي كي تكون مفيدة، بل يمكن لتطور صغير أن يكون له تأثيرا ايجابيا كبيرا بل ويستحق الاشادة أيضا.

لقد ذكرت مسبقا أن مشروع Digital Matatus كان في نيروبي، أنا معجب بشدة بالمشروع وكان لي الشرف أن أكون واحدا ممن شاركوا به منذ بدايته. هل بامكانك ان تصف لنا كيف تم تطبيق هذا المشروع؟ وكيف كانت “مواصلة للقاهرة” مختلفة؟

محمد حجازي: لقد تعرفت على Digital Matatus من خلال كتاب مجاني على الإنترنت يسمي “مابعد الشفافية” أو “Beyond Transparency” ، وعلمت الكثير بعد ذلك من خلال مصارد أخرى تهتم بالعمران مثل Wired و Atlantic و Guardian و العديد من الأوراق العلمية الأخري أيضا.

ظل الفريق هناك لأشهر متعددة يستخدم The Matatus لتسجيل آلاف المحطات ومئات الطرق بواسطة تطبيق خاص وجهاز تحديد المواقع الجغرافية GBS.

وطلبنا النصيحة من أحد الاكاديميين في احدي الجامعات المشاركة في المشروع جاكلين كلوب الأستاذ بمعهد التطوير الحضرى المستدام بجامعة كولومبيا، وسارة ويليامز مديرة معمل تصميم البيانات المدنية بمعهد ماساتشوتس للتقنية، (تنويه: دكتور كلوب هي أيضا مستشار ب “القاهرة من الأساس”).

ومن هنا عرفنا مدي اهمية المشاركة المؤسسية “مشاركة المؤسسات” لتنفيذ هذا العمل بنجاح.

اصطفاف عدد من الميكروباصات أسفل كوبري الدقي العلوى “رخصة المشاع الإبداعى CC-0”.

أحد التحديات التي نواجهها هنا في القاهرة انها تصل تقريبا إلى ثلاث أضعاف نيروبي، فبخلاف Matatus نيروبي ، فان شبكة المواصلات بالقاهرة لا ترتكز بشكل أساسي على الميكروباصات فقط، حيث تحتوي القاهرة على عددا كبيرا من وسائل النقل الجماعي المختلفة مثل المترو، والاتوبيسات، والميكروباصات بالإضافة إلى السير على الأقدام واشكالا أخرى من طرق التنقل التي لا تعتمد على السيارة، والتي عادة ما تهمل عندما يتم التحدث عن النقل.

الميكروباصات لديها شخصية فريدة في القاهرة خصوصا عن أي مكان آخر، حيث يدرك الناس هنا أنهم دائما الخيار الأسرع وغالبا الأرخص أيضا، ولكن في أحيان أخرى ينظر اليهم كتلوث، وكسائقين عنيفين مسببين للحوادث، وكباحث يعلم أن هذا النظام برمته عالي التكيف لقانون العرض والطلب، ولا يرتكز في مخططه على أي شخص، ولذلك فإن أحد الأسئلة التي نحاول الاجابة عنها في بحثنا هو تحليل مقاومة هذا النظام عند مواجهة ما هو غير متوقع.

بدأنا بتخطيط مسارات عدد من الميكروباصات، ونظرنا إلى البيانات ولاحظنا انه لا بدَّ من ان نعيد مراجعة خطة عملنا، وجدنا من خلال بحثنا أن من أجل أن تقوم “مواصلة للقاهرة” بوضع معلومات ذات معني في أيدي المواطنين، فيجب أن يعمل المشروع بشكل أكبر، وأن يتعرض لكافة وسائل النقل الجماعي. سيكون علينا أن نخطط النظام بأكمله.

هذا عمل كبير، كيف يمكن لفريق بحثي من 8 باحثين فقط أن يقوم بتخطيط شبكة المواصلات بكاملها لواحدة من أكبر المدن في العالم؟

محمد حجازي: الاجابة باختصار هي خطوة بخطوة، فريقنا المكون من ثمانية أفراد هم في معظمهم من المتطوعين، ولن نستطيع إحراز أي تقدم إذا ما حاولنا تخطيط النظام باكمله دفعة واحدة، لذلك فقد قسمنا هذا المشروع الضخم إلى العديد من المراحل الصغيرة، كانت المرحلة الاولي هي نشر البيانات والمعلومات الكاملة عن نظام النقل بواسطة المترو، وهذه المرحلة بالفعل تم انجازها ويستطيع الآن مطورى البرمجيات الخاصة بتخطيط الرحلات التي تشمل المترو باستخدامها للقيام بعملهم. ولقد بدأنا بالجزء الأسهل من المشروع لكي نثبت لأنفسنا وللأخرين أيضا أن لدينا بالفعل شيء مهم وذا معني لنساهم به.

قام البنك الدولي برفع مسارات 450 أتوبيس نقل عام من مجمل 880 مسار وأيضا نظام المترو باكمله، ولكنه لم يتضمن أي معلومات عن المحطات والمواقف وأماكنها.

(الصورة والمشروع كما هو موضح بموقع البنك الدولي)

الخطوة التالية كانت الاتوبيسات المملوكة للحكومة، وكان البنك الدولي بالفعل قد اجري مشروعا سابقا بتحديد مسارات اتوبيسات النقل العام بالقاهرة بواسطة نظام تحديد المواقع الجغرافية GIS ، ونظرا لاتاحة البنك الدولي لتلك المعلومات الخاصة به فاننا نعمل الآن على وضع بيانات كاملة بنظام GTFS للاتوبيسات.

حسام، ان اسهامنا هو أن نستنتج القواعد والانظمة التي تخبرنا بما نريد معرفته عن كيفية تحرك الناس داخل المدينة. لكي نفهم المنطق وراء. خارج نطاق السيطرة، لكي نري هيكل هذا النظام المعقد يجب أن نجمع العديد والعديد من البيانات، وتقوم بتحليلها وتنقيتها من الشوائب. ربما نمت هذه المدينة بشكل عضوي، ولكنها ونظام المواصلات الخاص بها نموا تبعا لقواعد ما، نحن نقوم بكتابة هذه القواعد لاول مرة كبيانات للأتوبيسات بنظام GTFS، وسيكون هذا خطوة ضخمة للأمام، ولكن ليست سوى وسيلة لهذا الهدف.

الهدف سيكون شيئا ياخذه الناس في نيويورك مثلا كشئ مستحق مسبقا. وهو نظام تخطيط رحلات سهل الوصول اليه متاح للإستخدام في عدة منصات وفي متناول اليد.

مثل Digital Matatus فنحن في “مواصلة للقاهرة” جزء من حوار عالمي دائر حول ديموقراطية التكنولوجيا، نحن نتعلم كيف نضع مقاييس عالمية لاستخدام تكنولوجيا مثل GTFS

التي تم تصميمها كي تعمل في دولا مثل الولايات المتحدة الامريكية وأوروبا حتى تعمل أيضا في دول العالم النامي.

وماذا بعد ذلك؟ وما نوع الإستقبال الذي قوبلتم به أيضا؟

محمد حجازي: المرحلة القادمة تتوقف على التمويل والشراكات، نحن بحاجة الى اختبارها ميدانيا لكل من الاتوبيسات التى تملكها الحكومة والميكروباص على حد سواء. لازل هناك الكثير من العمل لنقوم به.

الناس فى كجال التخطيط هنا فى القاهرة متحمسون لهذا المشروع، ولكن لأن آخرين لم ينجحوا فى القيام بذلك مسبقا فانهم ليسوا على يقين من أنه يمكن القيام به. وفي الحقيقة فان الكثيرون يشيدون بنا لتبنينا منهجية بحثية واضحة، ذلك ونأمل ان يعطينا التشارك مع الجامعات والمؤسسات الدولية والهيئات الحكومية مصداقية أكبر للتحرك للأمام، ونبحث بنشاط حاليا عن فرص للتمويل وللمشاركة أيضا.

حدثني قليلا عنك، وعن خلفيتك التي قادتك ل “مواصلة للقاهرة”؟ وما الشيء الذي يجمع هذا الفريق سويا؟

فريق “مواصلة للقاهرة” من أعلي اليسار. محمد محروس، ا. جابر، إ عبيد، محمد حجازي، ر. زياد، أ حجازي. وأيضا ولكن غير موجودين بالصورة. ه. العقدة، ت. طه”

حسام: تجمعنا تجربتنا المشتركة بيننا وبين كل فرد يعيش بالقاهرة، المواصلات هي مصدر لتوتر غير محدود، التلوث وعدم اليقين دائما حول كيفية الوصول لجهة ما وكم ستستغرق من الوقت. فأفضل وسيلة لمعالجة ذلك هي من خلال وسائل النقل العامة، رغم أن هذا صعب على أي شخص ان يفهمه، أي شخص شهد تخطيط الرحلات على الإنترنت أو عند السفر للخارج يريد ان يكون بمقدوره فعل نفس الشيء عند العودة مرة أخرى إلى القاهرة.

محمد حجازي: نحن ثمانية أشخاص نعمل معا فى “مواصلة للقاهرة” وقد أتينا من خلفيات مختلفة، ولكن يجمعنا رغبتنا في البحث عن تطبيقات على أرض الواقع، انا خبير اقتصادى من خلال التدريب وعملت فى مجال تطوير البرمجيات. حسام نشأ في القاهرة ودرس التخطيط العمراني، باحثان في التخطيط العمراني، متخصص في GIS ، مطور اعمال ذو خبرة، ومتخصص في تكنولوجيا المعلومات يقوم بالعمل في اطروحة الدكتوراة الخاصة به. حتى الآن فكل ما وصلنا له من عمل تم اعتمادا على تمويلنا الذاتي وجهودنا التطوعية، فرغبتنا المشتركة في ابقاء هذه البيانات متاحة للجميع في سبيل المنفعة العامة هو ما جعل ارتباطنا كفريق وثيقا، ونبحث حاليا بنشاط عن مصادر أخرى للتمويل من أجل الابقاء على هذا ممكنا.

ما هو الشيء الأكثر أهمية الذى تذكره عن “مواصلة للقاهرة”؟

حسام: أكثر ما يمكن ذكره هنا هو كيف كان من الممكن لمجموعة من الباحثين ان يتركوا علامة على حياة ملايين الناس من خلال أن يضعوا نظام خرائط لمخططات الرحلات لوسائل النقل العام فى أيدى الجمهور، حتى في مدينة كبيرة مثل القاهرة. نامل أن نكون جزءا من مناقشة عامة حول كيفية عمل نظام النقل العام بالقاهرة فعلا، و لكى نبدأ لاحقا التفكير في كيفية تطوير نظام نقل معقد كالذي في القاهرة. نحن بالاساس باحثين، وعقود من الأبحاث أثبتت ان زيادة عدد السيارات، وتوسيع الطرق، وازالة الترام، ووبناء المدن الطرفية خارج المدينة لا يخفف الازدحام، وما يرتبط به ذلك أيضا من الآثار الاقتضادية والبيئية السلبية، نأمل أن يساهم عملنا في إيجاد خيارات نقل أسهل لجميع المصريين عند استخادمهم لوسائل النقل العام.

في مؤتمر LOTE5 سيناقش محمد حجازي “مواصلة للقاهرة” خلال دورة من دورات المؤتمر بشهر فبراير فى بروكسل.

]تم تحرير هذه المقابلة واختصارها[

Translation by: Abdelmonem Ibrahim, an Egyptian architect with a passion for architecture, technology and innovation.

عبدالمنعم ابراهيم

معمارى مصري مهتم بالعمارة والتكنولوجيا والابداع

Cairo from Below co-founder Nicholas Hamilton interviews Transport for Cairo co-founders Mohamed Hegazy and Houssam Elokda

Visualization of Cairo’s Buses and Metro – routes and stops by Transport for Cairo

How was the idea of Transport for Cairo born?

Houssam: I was walking down the street when I got a rambling call from my long-time friend Hegazy about a project in Nairobi he had just learned about. He told me about a team that had put together a map of the city’s “informal” microbus system and opened the data to all. It was called Digital Matatus. Hegazy said he thought we could bring the idea to Cairo where privately run microbuses cover a huge share of the city’s transportation needs. I was so excited about the idea that I stopped walking, went into the nearest coffee shop, and opened my laptop to start researching. I became obsessed with the question of how we–as private citizens–could provide millions of Egyptians access to useful knowledge about the existing transport network and empower them to use that knowledge to improve their daily lives. We established the basics of our research methodology and started Transport for Cairo that day!

What does data have to do with getting around a city? What are hoping to achieve with this project?

Houssam: The whole purpose of this project is to ease people’s access to public transport in Cairo. Before you can think about designing improvements to a transit system, you must first understand the system you have. We want to get this data to as many people as possible. We want public and private transit operators, researchers, private app developers and the public to make inquiries with this data, to understand the system as it is.

M. Hegazy: Look, if you go to a trip planning website like Google Maps or Bey2ollak–which is one of the most popular apps in Egypt today–they can only give you driving directions, or maybe walking. They can’t give you public transit options because no one has collected that information or made it accessible, so it encourages people to take a car because they don’t have reliable information on public transit options.

We started with the idea to map Cairo’s microbuses because no map exists thinking we could integrate that microbus information with the government owned bus and Metro systems. We quickly learned there isn’t complete information on the Metro or the government owned buses–let alone the microbuses–that is available to the public, app developers, or to researchers. You need standardized data about routes, stops, trip length and schedules to make a map and power trip planning software, a type of data programmers call GTFS or General Transit Feed Specification.

This isn’t easy in the best of circumstances, but you need to understand how huge and complex the transportation system in Cairo is. Greater Cairo is home to 18 million residents, 20 on weekdays and rapidly growing in both geography and population. The Metro has 61 stations; it is 65 km long and expanding. There are somewhere between 450 to 880 government owned bus lines, and those two systems don’t satisfy Cairo’s transport needs so we also have the additional transportation system of microbuses, which are further sub-categorized into ones with license to run on particular routes, unlicensed ones on particular routes, and unlicensed ones that run in general directions similar to a shared taxi. No one really knows how many run, what routes they follow, or how many people use informal bus system, but the assumption goes that it covers 40% of the city’s transport needs, which is on par with the public bus system.

How do Cairenes get transit information right now? How does this compare with other types of information access?

Hossam: Right now knowledge about the public transport system is mostly orally transmitted and there is a lot of uncertainty about the quickest option. Making transport data available will put knowledge of the fastest and cheapest routes at the touch of your fingers: you will be able to use apps on every smart phone to tell you how to get somewhere and how long it will take.

M. Hegazy: With the exception of the Metro, there is very little information for me as a citizen to access. The government publishes a PDF document with the public bus routes, but it ends there. Even if the data exists, it isn’t publicly accessible and can’t be used for trip planning.

Do you need a smartphone to benefit from Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: There is a big misconception that people in the developing world don’t have smart phones. In Egypt, smartphone usage is currently at 15.5 million users–who have data plans–and growing. Over the next three years, it is projected to increase to 28 million, or more than 50% of the adult pop of the country.

A privately operated minibus under license from the Egyptian authorities (Creative Commons CC-0)

M. Hegazy: Let me address another common misconception. Public transit users are not only of poor status, everyone uses public transit. People with smartphones are increasingly on public transit. This is true the world over where free wifi and cell service is being rolled out underground. Also, while we envision printed system maps could be produced, there is one final misconception worth addressing. Changes don’t have to be universal to be helpful: even an incremental improvement can have huge positive impact and be worthwhile.

You mentioned earlier the Digital Matatus project in Nairobi. I’m a big fan of the project and had the privilege of being involved in some of its early planning. Could you describe how that project unfolded and how Transport for Cairo is different?

M. Hegazy: I learned about Digital Matatus in the free, online book Beyond Transparency, and then learned more from online urban sources like Wired, Atlantic and Guardian and academic papers. The team there spent months riding the matatus recording thousands of stops and hundreds of routes with a custom app and GPS from sources. We subsequently met and sought advice from some of the university partners of the project such as Professor Jacqueline Klopp at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Urban Development, and Sarah Williams, Director of the Civic Data Design Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). [Disclosure: Professor Klopp is also an adviser to Cairo from Below]. From them we learned how important institutional partnerships would be to successfully implementing the work.

Microbuses lined up under the Dokki Flyover (Creative Commons CC-0)

One of the challenges we face here in Cairo is that the city is three or four times as populous and large as Nairobi. Unlike Nairobi and its matatus, Cairo’s system isn’t primarily centered on microbuses. Cairo has many types of mass transit: the Metro, buses and microbuses–in addition to walking and other forms of non-motorized transit which are often overlooked when talking about transportation.

The microbuses have a complex identity in Cairo and elsewhere. Here people know they are usually the fastest option and often the cheapest, but they are sometimes also viewed as polluting, and prone to aggressive drivers and accidents. As researchers we also recognize it is a system highly adaptive to supply and demand, and is not centrally planned by anyone. One of our research questions seeks to analyze the system’s resiliency in the face of the unexpected.

We started with mapping a couple of microbus routes, looked at the data and realized we had to revise our strategy. We found through our research that for Transport for Cairo to put meaningful data into the hands of citizens, the project needed to get way bigger and encompass all forms of mass transit data. We had to map the entire system.

This is a huge undertaking, how can a team of eight researchers map the entire transportation system of one of the world’s largest cities?

M. Hegazy: The short answer is step by step. Our team of eight mostly volunteers wouldn’t get anywhere if we tried to map the whole of Cairo at once so we broke the now much larger project into phases. The first phase was creating and publishing a full set of data for the Metro. That phase is done so people can now at least begin developing apps to provide trip planning that includes the Metro. We did the easiest part first to prove to ourselves and others that we had something meaningful to contribute.

The World Bank has mapped 450 of Cairo’s 880 public bus routes as well as the Metro system, but did not include information on stop locations (image and project described on World Bank website)

The next phase was government owned buses. The World Bank had done an earlier project on the GIS mapping of the official bus lines, but not stops, trip length or frequency so it wasn’t helpful in trip planning. Because the World Bank has been open to sharing their data, we are currently creating a full GTFS dataset for the buses. We can create a first version of this data without fieldwork. Stations may not be identified with a sign, but they emerge in practice.

Houssam: Our contribution is to deduce the rules and patterns that tell you most of what you need to know about how people move within the city: to understand the logic of a seemingly out of control system. To see the structure of this complex system you need to collect lots, and lots of data, analyze it and clean out the noise. The city may have grown organically, but it and its transport grew according to rules. We are writing those rules down for the first time in the form GTFS dataset for buses. This will be a huge step forward, but is only the means to the end.

The end is something people in New York and other large cities now take for granted: an accessible map and trip planning on multiple platforms in the palm of their hand. Like Digital Matatus, as Transport for Cairo we are part of a global discussion underway about how to democratize technology. We are learning how to make global technology standards like GTFS, which was designed for Europe and the US, work for the cities of the developing world.

What comes next? What kind of reception have you been getting?

M. Hegazy: The next phases will depend on funding and partnerships. We need to field test and verify this data for both the government owned buses and the microbuses. There is a lot of work still to do.

People in the planning domain here in Cairo are excited about this and they also are guarded because they aren’t sure it can be done and because others have tried this before. People give us credit for having such rigorous research methodology. Partnerships with universities, international organizations, and the Egyptian government will give us an even stronger legitimacy as we move forward. We are actively looking for both funding and partnerships.

Tell me a little about who you are and what from your personal backgrounds led you to start Transport for Cairo? What holds this group together?

Transport for Cairo Team: Clockwise, from top left: M. Mahrous, I. Gaber, E. Ebeid, M. Hegazy, R. Zeid and A. Hegazy (Missing are: H. Elokda, T. Taha).

Houssam: We were united by an experience shared among every person who’s lived in Cairo. Transportation is a source of infinite stress, pollution and uncertainty about how to get places and how long it will take. The best way to address this is through public transit, yet that same transit is difficult for anyone to understand. Anyone who has seen trip planning for mass transit online or when traveling abroad wants to be able to do it back home in Cairo.

M. Hegazy: There are eight of us working on TfC, we come from many backgrounds but are united by a passion for research with real world applications. I am an economist by training and had worked in software development. Houssam grew up in Cairo and came from research and urban planning background and works to improve cities around the world. Others in our team include a programmer, two urban researchers, a GIS professional, an experienced business developer and an information technology professional working on his PhD. Our work has been advanced entirely through self-funding and dedicated volunteer efforts. Ensuring that the data we generate remains open and accessible as a public good fundamentally glued our team together. We’re actively trying to attract grant funding to make this possible.

What is the most important thing to remember about Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: It is possible for a group of passionate researchers to touch millions of people’s lives through a project like putting smart trip planning for mass transit in the public’s hands, even in a city as large as Cairo. We hope to be a part of a conversation about how the city’s transportation actually functions so we can begin the later work of thinking about how to improve a transport system as complex as Cairo’s. We are fundamentally researchers and decades of research has shown that adding cars, widening roads, removing trams, and building peripheral cities outside of town does not alleviate congestion, and associated negative economic and environmental impacts. We hope our work contributes to people finding good public transit options for all Egyptians.

M. Hegazy will be discussing Transport for Cairo at a session of the LOTE5 conference in February in Brussels.

[This interview was edited and abridged]

Cairo from Below co-founder Nicholas Hamilton interviews Transport for Cairo co-founders Mohamed Hegazy and Houssam Elokda

Visualization of Cairo’s Buses and Metro – routes and stops by Transport for Cairo

How was the idea of Transport for Cairo born?

Houssam: I was walking down the street when I got a rambling call from my long-time friend Hegazy about a project in Nairobi he had just learned about. He told me about a team that had put together a map of the city’s “informal” microbus system and opened the data to all. It was called Digital Matatus. Hegazy said he thought we could bring the idea to Cairo where privately run microbuses cover a huge share of the city’s transportation needs. I was so excited about the idea that I stopped walking, went into the nearest coffee shop, and opened my laptop to start researching. I became obsessed with the question of how we–as private citizens–could provide millions of Egyptians access to useful knowledge about the existing transport network and empower them to use that knowledge to improve their daily lives. We established the basics of our research methodology and started Transport for Cairo that day!

What does data have to do with getting around a city? What are hoping to achieve with this project?

Houssam: The whole purpose of this project is to ease people’s access to public transport in Cairo. Before you can think about designing improvements to a transit system, you must first understand the system you have. We want to get this data to as many people as possible. We want public and private transit operators, researchers, private app developers and the public to make inquiries with this data, to understand the system as it is.

M. Hegazy: Look, if you go to a trip planning website like Google Maps or Bey2ollak–which is one of the most popular apps in Egypt today–they can only give you driving directions, or maybe walking. They can’t give you public transit options because no one has collected that information or made it accessible, so it encourages people to take a car because they don’t have reliable information on public transit options.

We started with the idea to map Cairo’s microbuses because no map exists thinking we could integrate that microbus information with the government owned bus and Metro systems. We quickly learned there isn’t complete information on the Metro or the government owned buses–let alone the microbuses–that is available to the public, app developers, or to researchers. You need standardized data about routes, stops, trip length and schedules to make a map and power trip planning software, a type of data programmers call GTFS or General Transit Feed Specification.

This isn’t easy in the best of circumstances, but you need to understand how huge and complex the transportation system in Cairo is. Greater Cairo is home to 18 million residents, 20 on weekdays and rapidly growing in both geography and population. The Metro has 61 stations; it is 65 km long and expanding. There are somewhere between 450 to 880 government owned bus lines, and those two systems don’t satisfy Cairo’s transport needs so we also have the additional transportation system of microbuses, which are further sub-categorized into ones with license to run on particular routes, unlicensed ones on particular routes, and unlicensed ones that run in general directions similar to a shared taxi. No one really knows how many run, what routes they follow, or how many people use informal bus system, but the assumption goes that it covers 40% of the city’s transport needs, which is on par with the public bus system.

How do Cairenes get transit information right now? How does this compare with other types of information access?

Hossam: Right now knowledge about the public transport system is mostly orally transmitted and there is a lot of uncertainty about the quickest option. Making transport data available will put knowledge of the fastest and cheapest routes at the touch of your fingers: you will be able to use apps on every smart phone to tell you how to get somewhere and how long it will take.

M. Hegazy: With the exception of the Metro, there is very little information for me as a citizen to access. The government publishes a PDF document with the public bus routes, but it ends there. Even if the data exists, it isn’t publicly accessible and can’t be used for trip planning.

Do you need a smartphone to benefit from Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: There is a big misconception that people in the developing world don’t have smart phones. In Egypt, smartphone usage is currently at 15.5 million users–who have data plans–and growing. Over the next three years, it is projected to increase to 28 million, or more than 50% of the adult pop of the country.

A privately operated minibus under license from the Egyptian authorities (Creative Commons CC-0)

M. Hegazy: Let me address another common misconception. Public transit users are not only of poor status, everyone uses public transit. People with smartphones are increasingly on public transit. This is true the world over where free wifi and cell service is being rolled out underground. Also, while we envision printed system maps could be produced, there is one final misconception worth addressing. Changes don’t have to be universal to be helpful: even an incremental improvement can have huge positive impact and be worthwhile.

You mentioned earlier the Digital Matatus project in Nairobi. I’m a big fan of the project and had the privilege of being involved in some of its early planning. Could you describe how that project unfolded and how Transport for Cairo is different?

M. Hegazy: I learned about Digital Matatus in the free, online book Beyond Transparency, and then learned more from online urban sources like Wired, Atlantic and Guardian and academic papers. The team there spent months riding the matatus recording thousands of stops and hundreds of routes with a custom app and GPS from sources. We subsequently met and sought advice from some of the university partners of the project such as Professor Jacqueline Klopp at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Urban Development, and Sarah Williams, Director of the Civic Data Design Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). [Disclosure: Professor Klopp is also an adviser to Cairo from Below]. From them we learned how important institutional partnerships would be to successfully implementing the work.

Microbuses lined up under the Dokki Flyover (Creative Commons CC-0)

One of the challenges we face here in Cairo is that the city is three or four times as populous and large as Nairobi. Unlike Nairobi and its matatus, Cairo’s system isn’t primarily centered on microbuses. Cairo has many types of mass transit: the Metro, buses and microbuses–in addition to walking and other forms of non-motorized transit which are often overlooked when talking about transportation.

The microbuses have a complex identity in Cairo and elsewhere. Here people know they are usually the fastest option and often the cheapest, but they are sometimes also viewed as polluting, and prone to aggressive drivers and accidents. As researchers we also recognize it is a system highly adaptive to supply and demand, and is not centrally planned by anyone. One of our research questions seeks to analyze the system’s resiliency in the face of the unexpected.

We started with mapping a couple of microbus routes, looked at the data and realized we had to revise our strategy. We found through our research that for Transport for Cairo to put meaningful data into the hands of citizens, the project needed to get way bigger and encompass all forms of mass transit data. We had to map the entire system.

This is a huge undertaking, how can a team of eight researchers map the entire transportation system of one of the world’s largest cities?

M. Hegazy: The short answer is step by step. Our team of eight mostly volunteers wouldn’t get anywhere if we tried to map the whole of Cairo at once so we broke the now much larger project into phases. The first phase was creating and publishing a full set of data for the Metro. That phase is done so people can now at least begin developing apps to provide trip planning that includes the Metro. We did the easiest part first to prove to ourselves and others that we had something meaningful to contribute.

The World Bank has mapped 450 of Cairo’s 880 public bus routes as well as the Metro system, but did not include information on stop locations (image and project described on World Bank website)

The next phase was government owned buses. The World Bank had done an earlier project on the GIS mapping of the official bus lines, but not stops, trip length or frequency so it wasn’t helpful in trip planning. Because the World Bank has been open to sharing their data, we are currently creating a full GTFS dataset for the buses. We can create a first version of this data without fieldwork. Stations may not be identified with a sign, but they emerge in practice.

Houssam: Our contribution is to deduce the rules and patterns that tell you most of what you need to know about how people move within the city: to understand the logic of a seemingly out of control system. To see the structure of this complex system you need to collect lots, and lots of data, analyze it and clean out the noise. The city may have grown organically, but it and its transport grew according to rules. We are writing those rules down for the first time in the form GTFS dataset for buses. This will be a huge step forward, but is only the means to the end.

The end is something people in New York and other large cities now take for granted: an accessible map and trip planning on multiple platforms in the palm of their hand. Like Digital Matatus, as Transport for Cairo we are part of a global discussion underway about how to democratize technology. We are learning how to make global technology standards like GTFS, which was designed for Europe and the US, work for the cities of the developing world.

What comes next? What kind of reception have you been getting?

M. Hegazy: The next phases will depend on funding and partnerships. We need to field test and verify this data for both the government owned buses and the microbuses. There is a lot of work still to do.

People in the planning domain here in Cairo are excited about this and they also are guarded because they aren’t sure it can be done and because others have tried this before. People give us credit for having such rigorous research methodology. Partnerships with universities, international organizations, and the Egyptian government will give us an even stronger legitimacy as we move forward. We are actively looking for both funding and partnerships.

Tell me a little about who you are and what from your personal backgrounds led you to start Transport for Cairo? What holds this group together?

Transport for Cairo Team: Clockwise, from top left: M. Mahrous, I. Gaber, E. Ebeid, M. Hegazy, R. Zeid and A. Hegazy (Missing are: H. Elokda, T. Taha).

Houssam: We were united by an experience shared among every person who’s lived in Cairo. Transportation is a source of infinite stress, pollution and uncertainty about how to get places and how long it will take. The best way to address this is through public transit, yet that same transit is difficult for anyone to understand. Anyone who has seen trip planning for mass transit online or when traveling abroad wants to be able to do it back home in Cairo.

M. Hegazy: There are eight of us working on TfC, we come from many backgrounds but are united by a passion for research with real world applications. I am an economist by training and had worked in software development. Houssam grew up in Cairo and came from research and urban planning background and works to improve cities around the world. Others in our team include a programmer, two urban researchers, a GIS professional, an experienced business developer and an information technology professional working on his PhD. Our work has been advanced entirely through self-funding and dedicated volunteer efforts. Ensuring that the data we generate remains open and accessible as a public good fundamentally glued our team together. We’re actively trying to attract grant funding to make this possible.

What is the most important thing to remember about Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: It is possible for a group of passionate researchers to touch millions of people’s lives through a project like putting smart trip planning for mass transit in the public’s hands, even in a city as large as Cairo. We hope to be a part of a conversation about how the city’s transportation actually functions so we can begin the later work of thinking about how to improve a transport system as complex as Cairo’s. We are fundamentally researchers and decades of research has shown that adding cars, widening roads, removing trams, and building peripheral cities outside of town does not alleviate congestion, and associated negative economic and environmental impacts. We hope our work contributes to people finding good public transit options for all Egyptians.

M. Hegazy will be discussing Transport for Cairo at a session of the LOTE5 conference in February in Brussels.

[This interview was edited and abridged]

[Note: Complete text in English below]

فيما يلي مقتطفات من مقال “محيط العاصمة القاهرة : الفصل المتطرف ” لكاتبه عبدالبصير محمد، لقراءة نص المقال كاملاً اتبع الرابط في الأسفل.

تكشف أنماط التوسع العمراني لمنطقة العاصمة القاهرة عن مدينة مفتتة لأجزاء غير متجانسة، فبإعتباري متخصص تخطيط عمراني وأيضاً قاهري، فأنا أميل إلي توصيف المدينة كسلسلة من الجزر الصغيرة المنعزلة عن بعضها بحواجز مادية مُحكمة: جدران، طرق سريعة، كباري عُلوية، مواقع عسكرية، وجهات مائية مهجورة، مواقف سيارات وأراضي شاغرة تتشارك جميعها في مدينة سمتها الأساسية نقص الاتساق والتجانس، بالإضافة إلي عدم وجود أماكن عامة تستوعب الفئات المجتمعية المختلفة، بل وتقوم كل فئة اجتماعية بحصر نفسها في حي منفصل على الأحرى.

تاريخ حافل من الفصل العمراني

يعتبر الفصل و التمييز العمراني سمة متأصلة في تاريخ القاهرة، فالقاهرة الفاطمية ( 969 م) كانت مدينة مسورة بالجدران أنشأت للنُخبة الحاكمة بشكل حصري، وفي العصر العثماني ( م1517- م 1798)، كانت الحارة -حي سكني مسوَّر على الأغلب- هي وحدة العمران الأساسية للمدينة، حيث تقع الحارات الفقيرة على أطرافها بينما الحارات البرجوازية والثرية يمكن أن نجدها في المركز، وعلى حد قول عالمة الاجتماع المصرية نوال المسيري “فالعيش في حارة، المغلق منها على وجه الخصوص، كان كالعيش في مملكة خاصة بالمرء، فالمنطقة كانت تحت إشراف ولم يسمح لأي شخص من الخارج بالدخول”،واستمرت هذة المحركات في العصر المملوكي، فقام الأمراء بإحاطة ضواحي المدينة بتكتلات وسوروا بيوتهم بالحدائق كي يعزلوا أنفسهم عن عامة الشعب، ومنذ عهد أقرب، بالمدينة الخديوية (م1869) – والتي اعدت بشكل رئيسي للأجانب والمصريين الأثرياء- فشيدت على أرض شاغرة في غرب المدينة القديمة (إلا أنها احتوت على مساكن الطبقة العاملة في نهاية الأمر). إن دراسة تاريخ المدينة الحافل يوضح لنا أن القاهرة أشبه بالإناء المتصدع الذي تم حفر هذة الكسور في ذاكرته عبر القرون، وبنظرة خاطفة على تاريخ القاهرة الحديث يتضح لنا أن هذة الكسور مستمرة إلي يومنا هذا.

لنص المقال الكامل، اضغط هنا http://www.failedarchitecture.com/cairos-metropolitan-landscape-segregation-extreme/

عبدالبصير محمد معماري ومخطط عمراني، حصل على درجة الماجستير في التصميم والتخطيط العمراني من جامعة عين شمس، حيث يعمل على درجة الدكتوراه. يهتم محمد بدراسة تأثير المساحة العمرانية على المتجمع، متبنياً منهج تركيبي، بناء المساحة، وحالياً زميل في برنامج كارنيجي بالجامعة الأمريكية في واشنطن.

The following is an excerpt from Abdelbaseer Mohamed’s “Cairo’s Metropolitan Landscape: Segregation Extreme” article. Follow the link below the text for the full article.

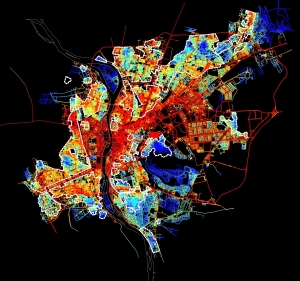

The urban growth patterns of the Cairo metropolitan area reveal a fragmented city of heterogeneous parts. As an urbanist and Cairo native I tend to see the city as a series of small islands isolated from one another by strong physical barriers. Walls, highways, flyovers, military sites, abandoned waterfronts, parking lots and vacant lands all contribute to a city that is characterised by a fundamental lack of cohesion. What is more, there is no public realm that accommodates different communities. Rather, each social group is confined to a separate enclave.

Spatial accessibility map for the urban agglomeration within the Ring RD. Red means integrated and accessible, while blue is segregated.

A long History of Urban Segregation

Urban segregation has been a continual feature of Cairo’s history. Fatimid Cairo (969) was a walled-city exclusively established for the ruling elite. In the Ottoman period (1517-1798), a Hara, mainly a gated residential quarter, was the basic urban unit of the city. Poor harat were located on the peripheries, while the wealthy bourgeois could be found in the centre. As Egyptian sociologist Nawal al-Messiri puts it, ‘Living in a hara, especially a closed hara, was like living in one’s own kingdom. The area was supervised and no person from the outside could enter’. These dynamics persisted into the Mamluk period, during which emirs would cluster around the outskirts of the city and surround their houses with gardens to segregate themselves from the citizens. More recently, the Khedivial city (1869), which was intended mainly for foreigners and wealthy Egyptians, was erected on vacant land west of the old city (although it eventually came to house the working class). By studying the city’s long history it becomes clear that Cairo is like a cracked vase, where fractures over many centuries have been etched into its physical memory. A cursory look at the more recent history of Cairo reveals that these fractures have persisted into the modern day.

Click here for the full article: http://www.failedarchitecture.com/cairos-metropolitan-landscape-segregation-extreme/

Abdelbaseer A. Mohamed is an architect and urban planner. Mohamed received his MSc in Urban planning and Design from Ain Shams University, where he is currently working on his PhD. He is mainly interested in studying the influence of urban space on society adopting a configurational approach, space syntax. Mohamed is currently a Carnegie fellow at American University in Washington.

Translation credit: Radwa Yassin is a fresh Building Engineering graduate from Ain Shams University. Yassin is specialized in Environmental and Sustainable Design, and is currently working as a Business development and Proposals Engineer. She is mainly interested in integrated solutions for planning and designing cities and buildings.

رضوى ياسين مهندسة بناء حديثة التخرج من جامعة عين شمس، متخصصة في التصميم البيئي المستدام، وتعمل حالياً كمهندسة عطاءات وتنمية أعمال. تهتم ياسين بدراسة الحلول المتكاملة لتخطيط وتصميم المدن والمباني.

[Note: Complete text in English below]

لال سبع سنوات، ستصبح هناك قاهرة جديدة “جديدة”، إنها العاصمة الجديدة التي سوف يتم بناءها في صحراء مصر الشرقية لتحوي مساكن، وظائف، متنزهات، مساجد وكنائس وجديدة. كل شئ جديد. قد تبدو هذة الفكرة غريبة للكثير من الناس، ولكن ليس للمصريين، فقد تبدلت العاصمة المصرية 24 مرة عبر ال5,000 سنة الماضية، حيث كان كل تبديل منهم بقصد تقليل الكثافة السكانية المركزية وتجنب الازدحام، وعلى الرغم من تكرر حدوث هذة المشاكل مراراً وتكراراً، إلا أن اقتراح الحل نفسه مازال مستمراً.

أعلنت الحكومة المصرية في مارس 2015 عن عقد شراكة مع شركة إماراتية لتمويل إنشاء العاصمة الجديدة، وطبقاً للحكومة المصرية، فإن الهدف الأساسي لهذة المدينة هو تخفيف الإزدحام و “التكدس السكاني” في القاهرة خلال الأربعين سنة القادمة، وسوف تقوم هذة المدينة الجديدة بخلق 21 منطقة سكنية جديدة والتي ستوفر مساكن ل5 مليون شخصاً، وتحتوي هذة المدينة أيضاً على 650 مستشفى وعيادة خارجية،و 1250 مسجد وكنيسة وفندق ومركز تسوق، ومدينة ملاهي ضعف حجم ديزني لاند.

قد لا يدرك العديد مساوئ هذة الفكرة فور قراءتها، فما الضرر في بناء مدينة جديدة وتعمير الأرض الصحراوية؟ ما الضرر في تخفيف زحام العاصمة الحالية وتوزيع الكثافة السكانية للقاهرة؟ وما الضرر في إحتمالية خلق المزيد من فرص العمل لمواطنين الطبقات الشعبية والمتوسطة؟ أما الضرر الحقيقي، فهو غير-واقعية هذة الخطة، الضرر هو قيام شركة خاصة أجنبية ب”شراء” والسيطرة على أراضي مصرية، الضرر هو أن صراع المواطنين المصريين من الطبقات الشعبية والمتوسطة اليومي لعيش حياتهم سيظل مستمراً.

للقاهرة تاريخ حافل بمخططات تشييد مدن بالضواحي في محاولات لتخفيف التكدس السكاني، وفي معظم الأحيان تترك هذة المدن قبل اكتمالها وتهجر، و واقعياً في حال بنيت هذة المدينة بنجاح، فإنها ستصبح مدينة للطبقات العليا بشكل حصري، فالطبقات الشعبية وحتى المتوسطة لن تتحمل تكاليف العيش في هذة المدينة الفاخرة. نعم، تستطيع هذة المدينة بالفعل جذب السياح والمواطنين الأثرياء، ولكن ما هدفها الحقيقي إذا بقيت المشاكل نفسها في القاهرة “القديمة”؟ ما الغرض من إنشاء مدينة جديدة تتجاهل مشاكل مصر العمرانية وتمكن دائرة الفقر من البقاء؟

لم تعد أسعار الوحدات السكنية في مصر في متناول المواطن العادي، مما تسبب في تحول مناطق محدودي الدخل إلي تجويفات مركزية للفقر، فمن أجل تخفيف الإزدحام و”التكدس السكاني” في مدن مثل القاهرة، يجب على الحكومة أن تتوسع خارج نطاق المدينة وذلك عن طريق بناء مساكن إضافية كامتداد للمدينة الموجودة بالفعل، لا أن تقوم ببناء مركز إضافي منزعل، كما عليها أن تقوم بتلبية احتياجات المدن القائمة فعلياً.

إن بناء أي مدينة جديدة يجب أن يتمحور حول رفع اقتصاد البلد ومحاربة الفقر بدلاً من بناء مدينة جديدة للمباني الحكومية وخلق منطقة جذابة للسائحين، وعلى الحكومة المصرية أن تقوم بتعيين مهندسين محليين وشركات مصرية لتخطيط وبناء هذة المدينة بدلاً من إسناد المشروع لشركات أجنبية، فتحويل هذة المدينة الجديدة إلي مشروع محلي سيتيح فرص عمل للمواطنين كما سيساعد على التخفيف من حدة البطالة والفقر. بالإضافة إلي ذلك، تستطيع هذة المدينة الإسهام في زيادة الدخل القومي عن طريق تمكين المواطنين من البدء في الأعمال الصغيرة، وشراء الأراضي والشقق السكنية، وكسب أجور المعيشة. إن حلم بناء المدينة الجديدة واسترجاع مكانة مصر في العالم الخارجي لا يزال ممكناً، ولكن أولاً، يجب أن يقوم على إشراك عموم الشعب في بناء بلد أفضل لهم.

تخرجت سارة البري حديثاً من جامعة روتجرز، وهي حاصلة على درجة البكالوريوس في دراسات التخطيط والسياسة العامة ودراسات الشرق الأوسط، ومرشحة للحصول على درجة الماجستير في الإدارة العامة من جامعة روتجرز في التنمية الدولية والإقليمية.

In seven years, there will be a ‘new’ new Cairo. The new capital will be built in Egypt’s Eastern desert with new homes, new jobs, new parks, new mosques and churches, new everything. This may sound like a new idea to many people but not to Egyptians. Over the last 5,000 years, Egypt has had 24 capital city changes. Each move has intended to decrease the population in one area and avoid congestion. Despite these same problems occurring again and again, the same solution continues to be given.

In March 2015, the Egyptian government announced a partnership with a UAE based company to fund the creation of the new capital city. According to the Egyptian government, the purpose of this new city is to ease congestion and “overpopulation” in Cairo over the next 40 years. The new city will create 21 new residential districts that will house 5 million people. The city will also have over 650 hospitals and clinics, 1,250 mosques and churches, hotels, malls and a theme park double the size of Disneyland.

Many people may read this idea and not immediately realize its faults. What’s wrong with building a new city and urbanizing desert land? What’s wrong with decongesting the current capital and spreading out Cairo’s population? What’s wrong with potentially creating more jobs for the lower and middle class citizens? What is wrong is, the plan is unrealistic. What is wrong is, a non-Egyptian private company is ‘buying’ and controlling Egyptian land. What is wrong is, lower and middle class Egyptian citizens will still struggle to live their daily lives.

Cairo has a long history of creating satellite cities in an effort to decongest Cairo. The cities are often left unfinished and deserted. Realistically, if this city is successfully accomplished, it will become an upper class city that is closed off from others. Lower and even middle class citizens will still not be able to afford to live in such a luxurious city. Yes, it may attract tourists and wealthy residents, but what’s the purpose if the same problems remain in “old” Cairo? What’s the purpose of creating a new city that will neglect Egypt’s urban problems and enable the poverty cycle to continue?

Housing prices are no longer affordable for an average citizen living in Egypt and this has caused low-income areas to become pockets of centralized poverty. In order to ease congestion and “overpopulation” in cities like Cairo, the government needs to expand out of the cities by adding housing as an extension to an already existing city, not creating an additional isolated hub. They also need to address the needs of already existing cities.

Instead of building a new city for government buildings and creating an attractive city for tourists, any new city should be focused on elevating the country’s economy and decreasing poverty. The government in Egypt should hire local engineers and Egyptian companies to plan and build the city instead of contracting out to foreign companies. Making the new city a local project will provide jobs to Egyptian citizens and aid to alleviate unemployment and poverty. In addition, more revenue can be generated when cities provide local opportunities to start businesses, buy land and apartments and earn living wages. The dream of making the new city and restoring Egypt’s reputation to the outside world can still happen, but it should involve Egyptians improving their own country, first.

Sarah Elbery is a recent graduate of Rutgers University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Planning & Public Policy and Middle Eastern Studies. She is currently an MPA candidate at Rutgers University with a concentration in International and Regional Development.

Translation credit: Radwa Yassin is a fresh Building Engineering graduate from Ain Shams University. Yassin is specialized in Environmental and Sustainable Design, and is currently working as a Business development and Proposals Engineer. She is mainly interested in integrated solutions for planning and designing cities and buildings.

رضوى ياسين مهندسة بناء حديثة التخرج من جامعة عين شمس، متخصصة في التصميم البيئي المستدام، وتعمل حالياً كمهندسة عطاءات وتنمية أعمال. تهتم ياسين بدراسة الحلول المتكاملة لتخطيط وتصميم المدن والمباني.

[Note: Complete text in English below]

عندما تأتي السابعة صباحاً، يقوم أكثر من 3000 رجل وآمرأة، تماماً مثل إنجي حسين وماريز دوس، بالخروج مسرعين من مساكنهم للركض فوق أسطح القاهرة الخرسانية، فهم يستيقظون مبكراً لكي يتجنبوا الإثنا وعشرون مليون قاهري،ومركباتهم الأربعة ملايين برحلاتها التي تستغرق حدود الساعة، والسحابة السوداء الخبيثة المشبعة بالضباب الدخاني الكيميائي المسرطن الذي يخيم على المدينة كل خريف. فيركضون هرباً من جنون القاهرة، العاصمة التي قاربت على تاريخ إنتهاء صلاحيتها، حيث التوسع العمراني المفرط الذي أودع نحو 20 إلي 40 في المئة من القاهرة الكبرى إلى الخبز الأبيض الرخيص ومواسير الصرف الصحي المكسورة. ولكن التفت لأعلى! إنها الشمس، تلك الكرة الفلكية التي تلفح ريف مصر وتوَّلِد رياح الخماسين المخيفة، قد اتت لإنقاد القاهرة.

في أبريل 2014، تعهدت الحكومة المصرية بمليار دولار أمريكي لتنمية عدة مشاريع طاقة شمسية في أنحاء البلاد، هذا التعهد الذي جاء بعد شهرين من إعلان وزير الكهرباء السابق أحمد إمام عن خطة الحكومة لزيادة حصة الطاقة المتجددة إلي 20 في المئة بحلول عام 2020، إلي جانب تعريفة التغذية بالطاقة السخية التي أعلن عنها في سبتمبر، تعتزم مصر الحصول على 4,300 ميجا وات من الطاقة المتجددة، فإذا صارت الأمور كما الخطة، ستلحق مصر بالعديد من البلدان الأخرى كالولايات المتحدة،و السويد، وفرنسا على طريق توفير الطاقة المتجددة.

وبعد ستة أشهر، اتفقت الحكومة المصرية على التعاون مع SkyPower Global وتنمية الخليج الدولية (IGD) لاستثمار 5 مليار دولار لتوليد 3000 ميجا وات من مشاريع الطاقة الشمسية، يهدف المشروع إلي خلق 75 ألف فرصة عمل وتقليل النسبة المؤية للبطالة 13.4 في البلاد، تم توقيع عقد الشراكة في مؤتمر دعم وتنمية الإقتصاد المصري المنعقد بشرم الشيخ في مارس 2015 بحضور مفوضين لتمثيل اكثر من 112 دولة، حيث لعبت مصر بكروتها لجذب استثمارات أجنبية بقرابة 60 مليار دولار، فقد أعلن وزير الاستثمار المصري، أشرف سلمان، في اليوم الثالث للمؤتمر أن الحكومة قد حصلت على اتفاقات موقعة ب 38.2 مليار دولار، ومع ختام المؤتمر حصلت الحكومة على مذكرات تفاهم تصل إلي 92 مليار دولار، خصصت منها 24 في المئة لقطاع إنتاج الكهرباء والطاقة. يعتبر مؤتمر دعم وتنمية الاقتصاد المصري جزء من خطة اكبر أصدرتها الجمعية المصرية لصناعات الطاقة الشمسية (SIA-EGYPT) في مارس بعنوان “السوق المصري للطاقة الشمسية تعريفة التغذية بالطاقة – ما بعد 2015″، مما دفع اكثر من 174 شركة بما فيهم Masdar و SkyPower Global و ACWA Power و Terra Solarإلي الانطلاق مسرعين كالذباب المتلهف للحصول على وعود الحكومة المصرية المعسولة بوعود تعريفة التغذية بالطاقة وعقود التطوير المستقل (IPP)، هذا وقد اقتصرت سلسلة المشاريع الأولى على انتاج 20 ميجا وات، مما يعادل تقريباً عُشر ال2,300 ميجا وات التي تعتزم الحكومة توليدها من الطاقة الشمسية بحلول عام 2017، بينما اتجه عدد قليل من هذة الاستثمارات إلي مشروعات ذات نطاق أكبر في قطاعات الأشغال العامة ومزارع الطاقة الشمسية الضوئية العملاقة المتصلة بشبكات القاهرة الكهربائية، على سبيل المثال مشروع Solar Park لشركة Terra Solar لانتاج 800 ميجا وات، وتساهم مشروعات أخرى بمصفوفات طاقة شمسية أصغر حجماً، والبحوث التقنية والتصنيع والتدريب.

ومن ناحية أخرى، فضلت بعض الهيئات أن تعمل خارج إطار برنامج الجمعية المصرية لصناعات الطاقة الشمسية (SIA-EGYPT) لتعريفة التغذية بالطاقة، على سبيل المثال مشروع “مدن الطاقة الشمسية – Solar Cities” لتركيب سخانات شمسية للمياة في حية منشأة ناصر، كما يعتزم كلاً من البنك الأهلي المصري وبنك مصر تمويل أنظمة الطاقة الشمسية فوق الأسطح من خلال تقديم قروض بأسعار فائدة تترواح بين 4 إلى 8 في المئة، إن وحدات الطاقة الشمسية فوق الأسطح سوف تساهم في تخفيف الحمل على شبكات الكهرباء المنهكة التي باتت تعتمد بشكل متزايد على الغاز الطبيعي، ونجد أكثر المتضررين بفشل هذة الشبكات بشكل ملموس في الأحياء الفقيرة وعشوائيات القاهرة الكبرى، إن احتراق الغاز الطبيعي لتعزيز هذة الشبكات قد عكر أجواء القاهرة بهواء ملوث يقدره بعض الخبراء بما يعادل تدخين علبة سجائر يوماً.

تستطيع علاقة مصر الوليدة بالطاقة الشمسية أن تخرج البلاد من دائرة الاعتماد على مصادر الطاقة غير المتجددة المسببة للتلوث، فضلاً عن إثارة اهتمام دول اخرى بمنطقة الشرق الأوسط وبشكل خاص دول الخليج، ففي حال نجحت، قد تقود مصر نوع جديد من التمثيل الضوئي، حيث تستقبل البلاد ضوء الشمس المجمع في وديان من وحدات الطاقة الشمسية، وبدورها تتفتح أحياءها الفقيرة كزهور اللوتس.

ماريا راموس كاتبة حرة تعيش حالياً في شيكاجو، حصلت على درجة بكالوريوس الآداب في اللغة الإنجليزية من جامعة إلينوي بشيكاجو، ودرست الإتصالات كتخصص ثانوي، تدوَِن ماريا عن نصائح صديقة للبيئة، وإنجازات تكنولوجية، وأنماط الحياة الصحية النشيطة.

Come 7:00 A.M., more than 3,000 men and women like, Engi Hassaan and Mariz Doss, will tumble out of their apartments to jog atop the concrete of Cairo. They rise early to dodge the city’s 22 million residents, the four million automobiles and their one-hour commutes, and the insidious “black cloud” of carcinogenic smog that hangs over the city every autumn. They run to escape the craziness of Cairo, a capital city nearing its expiration date, where hyper-urbanization has consigned some 20 to 40 percent of Greater Cairo to cheap white bread and broken sewer pipes. But look up! The sun, that orb that bakes rural Egypt and generates the fearsome khamaseen wind, has come to save Cairo.

In April 2014, the Egyptian government pledged $1 billion USD to develop several nationwide solar power projects. The vow came just two months after former electricity minister Ahmed Emam announced that the country planned to increase its share of renewable energy to 20 percent by 2020. Along with a generous feed-in tariff announced in September, Egypt intends to procure 4,300 megawatts of renewable energy. If all goes as planned, Egypt will be following many other countries, such as the United States, Sweden and France, on the road to making renewable energy more available.

Six months later, the government of Egypt shook hands with SkyPower Global and International Gulf Development for a $5 billion investment to create 3,000 megawatts of utility-scale solar projects. The project aims to create 75,000 jobs and put a dent in the country’s 13.4 percent unemployment rate. The partnership was signed at the Economic Development Conference held at Egypt’s Sharm el-Sheikh resort in March 2015. Delegates representing more than 112 countries attended the conference, where Egypt played its cards to attract some $60 billion in foreign investment. By the third day of the conference, Egypt’s Minister of Investment, Ashraf Salman, could boast that the country had procured $38.2 billion in signed agreements. By the conclusion, Egypt had raked in $92 billion in Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs). About 24 percent of that went to the electricity and power generation sector. Egypt’s Economic Development Conference was part of a greater plan released by the Egypt Solar Industry Association (Egypt-SIA) in March 2015 titled, ” Egypt’s Solar Energy Market – FiT Program and Beyond 2015.” Masdar, SkyPower Global, ACWA Power, Terra Sola and 174 more, flew like eager flies to Egypt’s honey-dripping promises of feed-in tariffs and

merchant IPP schemes. The first round of accepted projects will generate 20 megawatts, almost one-tenth of the 2,300 megawatts of solar power that Egypt hopes to develop by 2017. A few of the investments are large-scale public works projects and giant photovoltaic solar farms connected to Cairo’s electrical grid, such as Terra Solar’s 800-megawatt “solar park.” Other projects will contribute through smaller solar arrays, technical research, manufacturing and training.

Some organizations, however, have chosen to work outside of Egypt-SIA’s FiT program. A grassroots example is Solar Cities, which installs solar hot water heaters in the neighborhood of Manshiet Nasr. Additionally, The National Bank of Egypt and Banque Misr both plan to finance rooftop solar systems by providing loans with 4-8 percent interest rates. Rooftop solar units will help wean the country off its overworked grid that has become increasingly dependent on natural gas. The failure of that grid is felt the worst in the slums of Greater Cairo. The natural gas burned to sustain that grid has dirtied the Cairo atmosphere with air pollution that some experts liken to smoking a pack of cigarettes daily.

Egypt’s budding love affair with solar power could lift the country off its reliance on non-renewable and polluting energy sources, as well as ignite interest in other Middle East countries, particularly the Gulf States. If successful, Egypt could be leading a new type of photosynthesis, where the country basks in sunlight collected by PV parks, and in turn its poor neighborhoods blossom like lotus flowers.

Maria Ramos is a freelance writer currently living in Chicago. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from the University of Illinois at Chicago with a minor in Communication. She blogs about environmentally friendly tips, technological advancements, and healthy, active lifestyles.

Translation credit: Radwa Yassin is a fresh Building Engineering graduate from Ain Shams University. Yassin is specialized in Environmental and Sustainable Design, and is currently working as a Business development and Proposals Engineer. She is mainly interested in integrated solutions for planning and designing cities and buildings.

رضوى ياسين مهندسة بناء حديثة التخرج من جامعة عين شمس، متخصصة في التصميم البيئي المستدام، وتعمل حالياً كمهندسة عطاءات وتنمية أعمال. تهتم ياسين بدراسة الحلول المتكاملة لتخطيط وتصميم المدن والمباني.

[Note: Complete text in English below]

تحتوي القاهرة على ما يقرب من 70 كوبري علوي تم بناءهم لتخفيف المشكلة المرورية المزمنة لدى المدينة، وفي كثير من الأحيان تتحول هذة المنشآت إلى حواجز مادية وفجوات عملاقة تخل باستمرارية الشكل العام للمدينة، أضف إلي ذلك أن غالبية المساحات أسفل هذة الشوارع و الطرق السريعة المرفوعة غير مستغلة، قذرة، مظلمة، قبيحة، غير جذابة، متدهورة ومخيفة، وصارت مساحات مفتوحة تم إهدارها بالتجاهل والإهمال، وأصبحت أيضاً مجرد مساحات بينية أو “مواقع عدمية” تعمل كحد فاصل بين المناطق داخل المدينة. ولكن، ماذا إذا كان باستطاعة هذة المساحات العمل كعناصر تتدمج وتتكامل بدلاً من أن تقسم وتهدر الأراضي؟ ما هي إمكانية أن نقوم بتحويل المساحات السلبية، عديمة الحياة في القاهرة إلي أماكن ممتعة ،آمنة، ومتاحة للجميع؟

تتسم العديد من أحياء القاهرة بنُدرة المرافق والمساحات العامة، فتمثل المساحات اسفل الكباري بالنسبة لهذة الأحياء فرصة ثمينة للمجتمعات المحلية. فعوضاً عن استخدامها لنشاط إجرامي أو كمكبات للقمامة في الهواء الطلق، من الممكن تحويل هذة المساحات الميتة إلي أماكن رائعة للخدمات المجتمعية المختلفة والأنشطة الخارجية كالمكتبات المفتوحة، الفعاليات العامة، المعارض الفنية، والمطاعم ووسائل الترفيه. تستطيع هذة النوعية من المشاريع اللا-مركزية أن تعمل مراكز للترفيه، وأن توفر أماكن جذابة حيث يمكن أن يتفاعل مختلف فئات المجتمع. تخيل نوعاً آخر من القاهرة، مدينة بيئتها العمرانية تعاون المواطنين والمارة على المشاركة في المناسبات الثقافية والاجتماعية.

هناك الكثير من المبادرات العمرانية القائمة هدفها تحسين وتطوير مسطحات القاهرة الخضراء والمسطحات الحضرية، يهدف مشروع “ممرات وسط البلد” لمبادرة Cluster إلي إعادة تصميم ممرات وسط البلد الغير مستغلة بالقدر الكافي، بينما دشنت حملة “تلوين المدينة الرمادية” لإضافة البريق و الألوان لدرج وجدران القاهرة، وفي اعتقادي، ان الوقت قد حان لإطلاق مبادرة “أسفل الكوبري” للاستفادة من المساحات اسفل الكباري.

ويمكننا أن نجد مثال رئيسي على إمكانية استخدام المناطق أسفل الكباري بفاعلية في كراكاس، فنزويلا، حيث تباع الكتب تحت كوبري

Az Fuerzas Armadas، وتحولت المساحة اسفل الكوبري إلي منزه للكثير من الناس، كما توفر مساحة للتسلية بما في ذلك الألعاب العامة كالشطرنج.

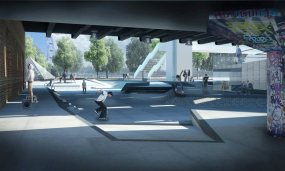

مثال بارز آخر قيد التشغيل هو متنزه برنسايد للتزلج Burnside Skatepark في بورتلاد، بولاية أوريجن، في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، حيث يقع المتنزه أسفل كوبري برنسايد على الضفة الشرقية لنهر ويلاميت، وبالرغم من أن بناء المتنزه تم بدون تصريح من قبل بعض المتزلجين، إلا أن الفكرة ألهمت العديد بالمدن الأمريكية باتخاذ مبادرات مشابهة. كما نستطيع ان نشاهد المزيد من النماذج الناجحة لمشروعات أسفل الكباري في جميع أنحاء العالم، من تورونتو إلى سلوفاكيا، لندن، ويسكونسن، زانستاد، وغيرهم.

إن تغيير هيئة هذة المناطق المهملة لن يتم بين ليلة وضحاها، فلكي يتم إعادة تصميم هذة المناطق المهدرة بالقاهرة، يجب على الحكومة أولاً أن تقوم بدراسة شاملة لتقييم الاستفادة المحتملة من هذة الأماكن الخارجية المفتوحة، وبشكل خاص الأراضي الخراب أسفل الكباري. فاستصلاح هذة المساحات سوف يضيف آلاف الأمتار المربعة من الأراضي القيمة لصالح مشروعات ثقافية،واقتصادية، واجتماعية. فباستطاعة هذة المساحات الحضرية -إذا صممت بشكل صحيح- أن توفر إطاراً موحداً لاعتراض الشكل المقسم للقاهرة الحديثة. ختاماً، إن شمول سكان الأحياء في عملية التحوييل العمراني لهذة الأماكن المنسية سيصبح المفتاح لخلق مساحات عامة شعبية للسكان المحيطين لينتفعوا منها وتكون تحت رعايتهم.

عبدالبصير محمد معماري ومخطط عمراني، حصل على درجة الماجستير في التصميم والتخطيط العمراني من جامعة عين شمس، حيث يعمل على درجة الدكتوراه. يهتم محمد بدراسة تأثير المساحة العمرانية على المتجمع، متبنياً منهج تركيبي، بناء المساحة، وحالياً زميل في برنامج كارنيجي بالجامعة الأمريكية في واشنطن.

There are almost 70 flyovers in Cairo that have been built to alleviate the city’s chronic traffic problem. These structures are often strong physical barriers or giant holes that disrupt the overall continuity of the city’s physical form. Furthermore, most of the spaces under these elevated freeways and roadways are left underused, dirty, dark, ugly, unattractive, deteriorating and frightening. They become wasted outdoor spaces that are ignored and neglected . They also become in-between spaces or ‘non-places’ that divide territories within the city. But what if these spaces could work as unifying and integrating objects, rather than dividing waste land? How can we transform negative spaces, devoid of life, in Cairo into fun, safe places open to all?

Many neighborhoods in Cairo are characterized by a lack of public amenities and space. For these neighborhoods under-bridge spaces offer a precious opportunity for local communities. Instead of being used for criminal activity or outdoor landfills, these dead spaces can be transformed into fantastic venues for various community facilities and outdoors activities such as pop-up libraries, public events, art galleries, canteens, and recreation. These kinds of anti-territorial projects could work as entertainment hubs and provide an inviting place where different groups of people can interact with one another. Imagine another kind of Cairo, a city whose physical environmental helps locals and passers-by to engage in open for cultural and social functions.

There are many already existing urban initiatives that aim to improve the landscape and townscape of Cairo. Cluster’s ‘Cairo Downtown Passages’ aims to redesign underused downtown passageways, while the ‘Coloring a Gray City’ campaign was launched to add brightness and color to Cairo’s staircases and walls. I believe it is time to launch an ‘Under Bridge’ initiative to utilize areas beneath flyovers.

A prime example of the potential for actively using areas under bridges can be seen in Caracas, Venezuela where books are being sold under the Av Fuerzas Armadas flyover. The space under the bridge has become a hangout spot for many people and provides a space for recreation, including public games of chess.

The street chess players under the bridge on

Fuerzas Armadas avenue. Source: caracasshots.blogspot.com

Another iconic example of action is Burnside Skate Park in Portland, Oregon, USA. The park is located under the Burnside Bridge on the east side of the Willamette River. Even though the skatepark was built by skaters without permission, the idea has inspired similar action in under bridge areas in many American cities.

More examples of successful under-bridge projects can be seen around the world from Toronto, to Slovakia , London, Wisconsin, Zaanstad and more.

Southbank skate park under Hungerford Bridge, London. Source: http://www.timeout.com

The transformation of these neglected areas won’t happen overnight. In order to redesign lost spaces in Cairo, the government must first conduct a thorough study of the usability of outdoor spaces, especially the wasteland beneath overpasses. Reclaiming these lost spaces will add thousands of square meters of valuable land for the benefit of cultural, economic and social projects. If designed properly, these urban spaces could provide a unifying framework to challenge the fragmented form of modern Cairo. Lastly, involving local people in the urban transformation process of these forgotten spaces will be key to creating popular public spaces that will be utilized and cared for by the surrounding residents.

Abdelbaseer A. Mohamed is an architect and urban planner. Mohamed received his MSc in Urban planning and Design from Ain Shams University, where he is currently working on his PhD. He is mainly interested in studying the influence of urban space on society adopting a configurational approach, space syntax. Mohamed is currently a Carnegie fellow at American University in Washington.

Translation credit: Radwa Yassin is a fresh Building Engineering graduate from Ain Shams University. Yassin is specialized in Environmental and Sustainable Design, and is currently working as a Business development and Proposals Engineer. She is mainly interested in integrated solutions for planning and designing cities and buildings.

رضوى ياسين مهندسة بناء حديثة التخرج من جامعة عين شمس، متخصصة في التصميم البيئي المستدام، وتعمل حالياً كمهندسة عطاءات وتنمية أعمال. تهتم ياسين بدراسة الحلول المتكاملة لتخطيط وتصميم المدن والمباني.

شارع المعز لدين الله الفاطمى : حين يلتقى الماضى مع امتداد القاهرة العمرانى

[Note: Complete text in English below]

أثناء السير فى شارع المعز لدين الله فى القاهرة الفاطمية, يلاحظ السائر بعض من أعتق الأثار والقواعد الأساسية فى بناء القاهرة, من ثم أصبح شاهد على كيفية نمو المدينة وامتدادها إلى ما وراء حوائطها الأصلية حتى أصبحت اليوم قطب نمو يحتوى على أكثر من 20 مليون ساكن.

على امتداد الطريق يمر السائر بالأحياء القديمة بأهلها, الأسواق كخان الخليلى أو الأسواق على شارع الموسكى, الأزهر ومسجد الحسين ويصل أخيراً إلى محور تجارى مزدحم وبذلك يصبح فى شارع الأزهر.

السير على طول شارع المعز يعد قصة لتاريخ القاهرة الحاضر حتى الآن على حد سواء مع امتدادها العمرانى الذى لا يكل ولا يهدأ.

شارع المعز لدين الله هو جزء مما يعرف بإسم القاهرة التاريخية, بطريقة ما هى منطقة محددة ومثيرة للجدل بالإضافة إلى انها موقع تراثى عالمى تحت إشراف اليونسكو منذ 1979. قبل حصولها على هذا اللقب, المبانى والأثار فى تلك المنطقة كانت إما تحصل على إنتباه واهتمام قوى من الدولة أو يتم درجها فى المخططات العمرانية بدون خطط واضحة للحفاظ عليها, حمايتها أو إعادة تأهيلها. وقد أدى ذلك إلى خليط من المبانى المتهالكة منذ قرن من الزمان, إلى جانب المبانى المرتجلة والغير رسمية التى تركن بطريقة خطرة على بعضها البعض, وبقايا مبانى مهدمة فى الطرق الخلفية.

بعيداً عن كونها موقع تراث عالمى, بالتالى تقع تحت معايير حماية محددة, القاهرة التاريخية, تحديداً على طول شارع المعز, أصبحت هدف لعديد من المشروعات.

المقترح الأخير كان لتحويل شارع المعز إلى متحف مفتوح, فى مجهودات لإحياء القطاع الإقتصادى الرئيسى لمصر, السياحة.

مع تلك المقومات الضخمة, فإن الأعمال التى تمت على مدار السنين قد أثمرت فى تجميل الشارع والمجال المحيط به, بما فى ذلك إضافة طبقة لمعان جديدة للمبانى.

مع ذلك لم تأخذ أيا من تلك التحركات فى اعتبارها المكون الإجتماعى الذى يحافظ على بقاء وحيوية ذلك المكان.

المبانى ذات القيمة العالية وجزء من التراث الثقافى لذلك المكان يبدو وكأنه قد تم نسيانه, إلى الأن على الأقل, وقد أثير الشك حول ما إذا كانت تقنيات التجديد تراعى الأسس التى تعطى قيمة لتلك الأثار.

إذا أصبحت تلك المنطقة متحف مفتوح, فإن أى سائر, ما إذا كان سائح أو محلياً, متجولاً فى الطريق من نهاية إلى آخرى – باب الفتوح إلى باب زويلة – سوف يرى فقط ما قُدم لتتم رؤيته وسوف يشهد فقط تمثيل صغير لمنطقة قيمة تمتد إلى أبعد وأكثر من مجرد شارع واحد.

بالإضافة إلى أن مشروع المتحف المفتوح ومشروعات آخرى تركيزها الأساسى على المبانى, مع العمارة التاريخية للمنطقة, وبالتالى خلق فجوة هامة ما بين الأشخاص وتلك المنطقة.

بمساعدة المنظمات الدولية مثل هيئة المعونة الأمريكية, الأمم المتحدة ومؤسسة أغا خان الثقافية.

المنظمات المحلية مثل مجاورة والرُبع, قد تفاعلت مع السكان المحليين والتجار الذين أعطوا الحياة لذلك الشارع وللأحياء المجاورة.

هؤلاء الأشخاص ساهموا فى خلق طابع خاص للمكان بطريقة يومية وحيوية, من خلال أعمالهم, مهاراتهم, وحرفهم الفنية واليدوية, وبقصص وروابط الأسر, كما يمكن أن يرى من خلال رويات نجيب محفوظ على سبيل المثال.

أى إعادة تأهيل للمبانى على طول المعز وفى القاهرة التاريخية بحاجة إلى أن تأخذ فى الاعتبار الديناميكية اليومية لمثل تلك الأحياء الشعبية.

الفصل المتكرر لتلك القضايا يطرح سؤال عن الغرض من الحفاظ على تلك المنطقة كموقع تراث عالمى ومتحف مفتوح: هل ذلك الفراغ متاح ليتم عرضه وتحويله إلى متحف مفتوح, ولمن؟

السؤال الأكثر أهمية, رغبات من التى تخدمها تلك المشروعات؟

العلاقة ما بين السياح, التجار والسكان لابد من مراعتها, حيث يمكن تشكيل التاريخ بمختلف الخطابات ,سواء أن كانت شخصية, محلية أو عالمية.

هل يمكن القول أن باكتساب ذلك المكان لصفة التراث العالمى فإن لنا جميعاً ماضى مشترك , بإعتباره عالمى ؟

عندما يتم عرض الماضى من خلال خطاب معين, فإن ذلك يمكن أن يتلاعب بهوية المكان, والمحيط به, والتأثير ببطئ على الذكريات التى كان قد تم تصورها وتخيلها عن تاريخ شارع المعز.

هنا يكون الرابط ما بين الماضى, الهوية, وحكاية مكان لا بد من الحفاظ عليه بجانب أهله ودينامكياته وأسسه الثقافية.

الأخطر من أي طريق أخر هو أن يكون هناك انفصال متزايد ما بين الخطاب الرسمي والواقع داخل هذه الأحياء.

أصبح شارع المعز أيضاً منطقة يتمكن ساكنيها والمارين بها من الاختلاط معاً وإعادة توظيف المساحة العامة لتتوافق معهم بطريقتهم الخاصة. وبالتالى خلق مكان للمقابلات والإجتماعيات.

لا يزال فى محض الرؤية, إلى أى مدى ونتائج سيصل ذلك, حيث أن المشروعات قد اقتطعت وتم احيائها مرة أخرى إلى جانب الديناميكيات الإجتماعية لذلك المكان وللقاهرة الكبرى.

عند استخدام الماضى بجعله غير متحرك ومع ذلك متحرك بصورة كافية للتدخل والتغيير فى مخططات التنمية العمرانية للقاهرة, لابد من عدم نسيان الطبقات المتعددة – إجتماعيا, اقتصادياً, ثقافيا – والتى تشكل وتستمر فى جلب الحياة لشارع المعز وجعله مستحق للزيارة.

كتاب “الشارع العظيم, المعز لدين الله, القاهرة التاريخية” , من الحكومة المصرية ومهدى إلى فاروق حسنى, الوزير السابق للثقافة, من أجل تفاصيلى عن المشروع.

ليندا بيترهان ولدت ونشأت فى سويسرا, اهتمامها بالشرق الأوسط وشمال أفريقيا بدأ عندما بدأت فى دراسة اللغة العربية كطالبة واستمر فى النمو بعد ذلك عند قضائها سنة فى الأردن.

ليندا أكملت طريقها فى علم الإجتماع والإجتماعيات مع التركيز على نطاق الشرق الأوسط وشمال أفريقيا.

دراستها أتت بها إلى القاهرة, مصر حيث بدأت فى العمل على رسالتها.

صعقت بجمال مناظرها الطبيعية وتعقيداتها, أخذت ليندا اهتمام متزايد فى الدراسات العمرانية ودمجتها مع أخر عمل لها فى الماجيستير. تركز الأن على دمج الدراسات العمرانية مع العلاقات الإنسانية فى الشرق الأوسط وشمال أفريقيا.

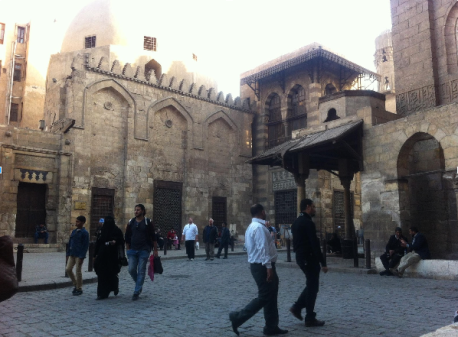

Al-Mu’izz li-Dîn Allah Street with renovated monuments; not all of monuments are open for visits – photo: LP

When walking down Al-Mu’izz li-Dîn Allah Street in Fatimid Cairo, one observes some of the most ancient monuments and foundations of Cairo, thus becoming a witness to how the city has developed and extended beyond its original walls to a megapole of more than 20 million inhabitants today. Along the way one passes old neighborhoods with their people, markets such as the Khân al-Khalili or ones along Muski street, Al-Azhar and Al-Hussein mosque, and finally comes to a busy commercial axis that has become Al-Azhar street. The walk along Al-Mu’izz li-Dîn Allah Street is both a story of Cairo’s ever-present past and its restless urban expansion.

Al-Mu’izz li-Dîn Allah Street is part of what is known as Historic Cairo, a somewhat debatable delimited area and a World Heritage Site under UNESCO since 1979. Before receiving this recognition, the buildings and monuments in this area had either not received great attention from the government or had been included in urban plans without a clear agenda for preservation, protection, or rehabilitation. This has led to a patchwork of century-old run-down buildings, along with improvised or informal buildings leaning dangerously against one another, and remnants of demolished buildings in the backstreets.

One can see a minaret and a mosque whose roof is damaged and disappears between the neighboring buildings. The contrast is obvious between the more “glamorous” parts of Al-Mu’izz street and its second half, which is cut by Al-Azhar street. All of this area is protected area under World Heritage Site regulations. Photo: LP

Despite being a World Heritage Site, thus being under specific protective regulations, Historic Cairo, specifically along Al-Mu’izz street, has been the target of several projects. The latest proposal is to make Al-Muizz street an open-air museum [1], in an effort to restore Egypt’s main economic sector, tourism. With such huge potential, actions taken over the past years have resulted in the beautification of the street and its space, including adding a new gloss to the buildings. Yet none of these actions have taken into account the social component of what keeps this place alive. Valuable buildings and part of this space’s cultural heritage seem nevertheless to have been forgotten, for now at least, and doubts have been raised about whether renovation techniques are respecting the structure and other elements that give value to these monuments. If this area becomes an open-air museum, then any walker, whether a tourist or a local, wandering down the street from one end to the other – Bab al-Futuh to Bab Zuwayla – would only see what is put forth to be seen and would only witness a small representation of a valuable area that stretches beyond one street.

Moreover, the open-air museum project and others have mainly focused on the buildings, emphasizing the historical architecture of this area, thus creating an important gap between the people and this space. With the help of international organizations such as USAID, UNESCO and The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, local organizations such as Megawra and Al-Rab3, have engaged with the civilian population and merchants who give life to this street and surrounding neighborhoods. These people contribute to the place’s character in a daily and lively manner, through their work, skills and art crafts, and family stories and ties, as can be seen through Naguib Mahfouz’s novels for instance.

Moreover, the open-air museum project and others have mainly focused on the buildings, emphasizing the historical architecture of this area, thus creating an important gap between the people and this space. With the help of international organizations such as USAID, UNESCO and The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, local organizations such as Megawra and Al-Rab3, have engaged with the civilian population and merchants who give life to this street and surrounding neighborhoods. These people contribute to the place’s character in a daily and lively manner, through their work, skills and art crafts, and family stories and ties, as can be seen through Naguib Mahfouz’s novels for instance.