Citizens Make a Difference Together at Transport for Cairo

Cairo from Below co-founder Nicholas Hamilton interviews Transport for Cairo co-founders Mohamed Hegazy and Houssam Elokda

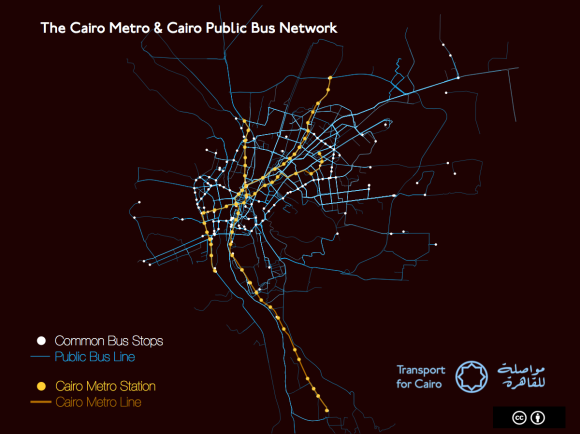

Visualization of Cairo’s Buses and Metro – routes and stops by Transport for Cairo

How was the idea of Transport for Cairo born?

Houssam: I was walking down the street when I got a rambling call from my long-time friend Hegazy about a project in Nairobi he had just learned about. He told me about a team that had put together a map of the city’s “informal” microbus system and opened the data to all. It was called Digital Matatus. Hegazy said he thought we could bring the idea to Cairo where privately run microbuses cover a huge share of the city’s transportation needs. I was so excited about the idea that I stopped walking, went into the nearest coffee shop, and opened my laptop to start researching. I became obsessed with the question of how we–as private citizens–could provide millions of Egyptians access to useful knowledge about the existing transport network and empower them to use that knowledge to improve their daily lives. We established the basics of our research methodology and started Transport for Cairo that day!

What does data have to do with getting around a city? What are hoping to achieve with this project?

Houssam: The whole purpose of this project is to ease people’s access to public transport in Cairo. Before you can think about designing improvements to a transit system, you must first understand the system you have. We want to get this data to as many people as possible. We want public and private transit operators, researchers, private app developers and the public to make inquiries with this data, to understand the system as it is.

M. Hegazy: Look, if you go to a trip planning website like Google Maps or Bey2ollak–which is one of the most popular apps in Egypt today–they can only give you driving directions, or maybe walking. They can’t give you public transit options because no one has collected that information or made it accessible, so it encourages people to take a car because they don’t have reliable information on public transit options.

We started with the idea to map Cairo’s microbuses because no map exists thinking we could integrate that microbus information with the government owned bus and Metro systems. We quickly learned there isn’t complete information on the Metro or the government owned buses–let alone the microbuses–that is available to the public, app developers, or to researchers. You need standardized data about routes, stops, trip length and schedules to make a map and power trip planning software, a type of data programmers call GTFS or General Transit Feed Specification.

This isn’t easy in the best of circumstances, but you need to understand how huge and complex the transportation system in Cairo is. Greater Cairo is home to 18 million residents, 20 on weekdays and rapidly growing in both geography and population. The Metro has 61 stations; it is 65 km long and expanding. There are somewhere between 450 to 880 government owned bus lines, and those two systems don’t satisfy Cairo’s transport needs so we also have the additional transportation system of microbuses, which are further sub-categorized into ones with license to run on particular routes, unlicensed ones on particular routes, and unlicensed ones that run in general directions similar to a shared taxi. No one really knows how many run, what routes they follow, or how many people use informal bus system, but the assumption goes that it covers 40% of the city’s transport needs, which is on par with the public bus system.

How do Cairenes get transit information right now? How does this compare with other types of information access?

Hossam: Right now knowledge about the public transport system is mostly orally transmitted and there is a lot of uncertainty about the quickest option. Making transport data available will put knowledge of the fastest and cheapest routes at the touch of your fingers: you will be able to use apps on every smart phone to tell you how to get somewhere and how long it will take.

M. Hegazy: With the exception of the Metro, there is very little information for me as a citizen to access. The government publishes a PDF document with the public bus routes, but it ends there. Even if the data exists, it isn’t publicly accessible and can’t be used for trip planning.

Do you need a smartphone to benefit from Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: There is a big misconception that people in the developing world don’t have smart phones. In Egypt, smartphone usage is currently at 15.5 million users–who have data plans–and growing. Over the next three years, it is projected to increase to 28 million, or more than 50% of the adult pop of the country.

A privately operated minibus under license from the Egyptian authorities (Creative Commons CC-0)

M. Hegazy: Let me address another common misconception. Public transit users are not only of poor status, everyone uses public transit. People with smartphones are increasingly on public transit. This is true the world over where free wifi and cell service is being rolled out underground. Also, while we envision printed system maps could be produced, there is one final misconception worth addressing. Changes don’t have to be universal to be helpful: even an incremental improvement can have huge positive impact and be worthwhile.

You mentioned earlier the Digital Matatus project in Nairobi. I’m a big fan of the project and had the privilege of being involved in some of its early planning. Could you describe how that project unfolded and how Transport for Cairo is different?

M. Hegazy: I learned about Digital Matatus in the free, online book Beyond Transparency, and then learned more from online urban sources like Wired, Atlantic and Guardian and academic papers. The team there spent months riding the matatus recording thousands of stops and hundreds of routes with a custom app and GPS from sources. We subsequently met and sought advice from some of the university partners of the project such as Professor Jacqueline Klopp at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Urban Development, and Sarah Williams, Director of the Civic Data Design Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). [Disclosure: Professor Klopp is also an adviser to Cairo from Below]. From them we learned how important institutional partnerships would be to successfully implementing the work.

Microbuses lined up under the Dokki Flyover (Creative Commons CC-0)

One of the challenges we face here in Cairo is that the city is three or four times as populous and large as Nairobi. Unlike Nairobi and its matatus, Cairo’s system isn’t primarily centered on microbuses. Cairo has many types of mass transit: the Metro, buses and microbuses–in addition to walking and other forms of non-motorized transit which are often overlooked when talking about transportation.

The microbuses have a complex identity in Cairo and elsewhere. Here people know they are usually the fastest option and often the cheapest, but they are sometimes also viewed as polluting, and prone to aggressive drivers and accidents. As researchers we also recognize it is a system highly adaptive to supply and demand, and is not centrally planned by anyone. One of our research questions seeks to analyze the system’s resiliency in the face of the unexpected.

We started with mapping a couple of microbus routes, looked at the data and realized we had to revise our strategy. We found through our research that for Transport for Cairo to put meaningful data into the hands of citizens, the project needed to get way bigger and encompass all forms of mass transit data. We had to map the entire system.

This is a huge undertaking, how can a team of eight researchers map the entire transportation system of one of the world’s largest cities?

M. Hegazy: The short answer is step by step. Our team of eight mostly volunteers wouldn’t get anywhere if we tried to map the whole of Cairo at once so we broke the now much larger project into phases. The first phase was creating and publishing a full set of data for the Metro. That phase is done so people can now at least begin developing apps to provide trip planning that includes the Metro. We did the easiest part first to prove to ourselves and others that we had something meaningful to contribute.

The World Bank has mapped 450 of Cairo’s 880 public bus routes as well as the Metro system, but did not include information on stop locations (image and project described on World Bank website)

The next phase was government owned buses. The World Bank had done an earlier project on the GIS mapping of the official bus lines, but not stops, trip length or frequency so it wasn’t helpful in trip planning. Because the World Bank has been open to sharing their data, we are currently creating a full GTFS dataset for the buses. We can create a first version of this data without fieldwork. Stations may not be identified with a sign, but they emerge in practice.

Houssam: Our contribution is to deduce the rules and patterns that tell you most of what you need to know about how people move within the city: to understand the logic of a seemingly out of control system. To see the structure of this complex system you need to collect lots, and lots of data, analyze it and clean out the noise. The city may have grown organically, but it and its transport grew according to rules. We are writing those rules down for the first time in the form GTFS dataset for buses. This will be a huge step forward, but is only the means to the end.

The end is something people in New York and other large cities now take for granted: an accessible map and trip planning on multiple platforms in the palm of their hand. Like Digital Matatus, as Transport for Cairo we are part of a global discussion underway about how to democratize technology. We are learning how to make global technology standards like GTFS, which was designed for Europe and the US, work for the cities of the developing world.

What comes next? What kind of reception have you been getting?

M. Hegazy: The next phases will depend on funding and partnerships. We need to field test and verify this data for both the government owned buses and the microbuses. There is a lot of work still to do.

People in the planning domain here in Cairo are excited about this and they also are guarded because they aren’t sure it can be done and because others have tried this before. People give us credit for having such rigorous research methodology. Partnerships with universities, international organizations, and the Egyptian government will give us an even stronger legitimacy as we move forward. We are actively looking for both funding and partnerships.

Tell me a little about who you are and what from your personal backgrounds led you to start Transport for Cairo? What holds this group together?

Transport for Cairo Team: Clockwise, from top left: M. Mahrous, I. Gaber, E. Ebeid, M. Hegazy, R. Zeid and A. Hegazy (Missing are: H. Elokda, T. Taha).

Houssam: We were united by an experience shared among every person who’s lived in Cairo. Transportation is a source of infinite stress, pollution and uncertainty about how to get places and how long it will take. The best way to address this is through public transit, yet that same transit is difficult for anyone to understand. Anyone who has seen trip planning for mass transit online or when traveling abroad wants to be able to do it back home in Cairo.

M. Hegazy: There are eight of us working on TfC, we come from many backgrounds but are united by a passion for research with real world applications. I am an economist by training and had worked in software development. Houssam grew up in Cairo and came from research and urban planning background and works to improve cities around the world. Others in our team include a programmer, two urban researchers, a GIS professional, an experienced business developer and an information technology professional working on his PhD. Our work has been advanced entirely through self-funding and dedicated volunteer efforts. Ensuring that the data we generate remains open and accessible as a public good fundamentally glued our team together. We’re actively trying to attract grant funding to make this possible.

What is the most important thing to remember about Transport for Cairo?

Houssam: It is possible for a group of passionate researchers to touch millions of people’s lives through a project like putting smart trip planning for mass transit in the public’s hands, even in a city as large as Cairo. We hope to be a part of a conversation about how the city’s transportation actually functions so we can begin the later work of thinking about how to improve a transport system as complex as Cairo’s. We are fundamentally researchers and decades of research has shown that adding cars, widening roads, removing trams, and building peripheral cities outside of town does not alleviate congestion, and associated negative economic and environmental impacts. We hope our work contributes to people finding good public transit options for all Egyptians.

M. Hegazy will be discussing Transport for Cairo at a session of the LOTE5 conference in February in Brussels.

[This interview was edited and abridged]

يسعدني حقًا أن أقول إن هذا المقال مثير للاهتمام للغاية

Great work! Will you publish your work to the public?

It would be interesting to have these maps for Cairo Transport, and will help locals a lot!

Thanks

Dear Mo. Elkhateeb,

Thank you for your interest. Yes, we will publish it as open data using GTFS format.

Regards.

Islam Gaber

Great initiative